|

Make lots of money by giving it away |

|

First published on LinkedIn 2nd September 2019 People often ask me, "how did Freeserve make any money?" They assume we must have been a loss-making internet company. Unfortunately, you won't know the story behind Freeserve unless you've met me, so here's a shortened, abbreviated version. I failed my exams at school and couldn't go to college. So, I looked around for a job and ended up at Dixons as a junior salesman, when it was still called Dixons Photographic. At the time, Dixons only sold photographic equipment. Dixons is now known as Currys. A big turning point for Dixons was when they started to sell home computers like the Commodore Vic 20 and Sinclair ZX80. The computer market exploded, and it seemed everyone in the country wanted to buy a home computer, including me. So with a month's salary, I bought a Commodore Vic 20 even though I didn't know what to do with it. I steadily moved up the corporate ladder and became the Manager of the Manchester store, the highest turnover store in the North of England. And then one day we received a memo from head office telling us that we had bought a small company called PC World with just four stores in London. |

|

After reading the memo, I decided there and then that I wanted to work in PC World. Luckily for me, the first new store north of London was opened in Leeds, close to where I live, and I became a manager there.

The market for these new PC's and software was enormous, and business was booming; everyone wanted a PC. I remember one-night customers queued until midnight for the launch of Windows 95, and we all wore t-shirts that said: "I was there at the start." My first PC was an IBM ThinkPad. A few months later I bought a modem because I'd heard about this thing called the internet. I asked the staff, "how do you get onto the internet?" and the answer was, "I don't know," everyone just shrugged their shoulders. Eventually, someone in the tech centre said, "Try Demon internet; they're supposed to be good." So, I phoned Demon and asked the guy, "what do I need to get onto the internet?" "You'll need a browser," said the man. "How do I get a browser?" I asked, "you can FTP it from our site," said the man. I was frustrated. I put the phone down. I now know that FTP stands for 'File Transfer Protocol', which means you have to be on the internet to download a browser; Demon was clearly for technical people. I didn't give up, and I eventually found a CD on a magazine cover for CompuServe, a big American company. So I installed the CD, set up my direct debit for £17.99 a month, and got onto the internet. When I got onto CompuServe, I thought, "Wow, this is fantastic, everyone will want to use the internet", and I reflected on my experience and had my eureka moment. I thought that if the staff couldn't tell me how to get onto the internet, thousands of customers a day must ask us the same question, and we say, "we don't know." So, suppose we become an 'Internet service provider' (ISP). In that case, we'll be able to do something that none of the competitors can do, and that is to get to the customers first because we've just sold them the thing that allows them to get onto the internet, the computer. We can hand customers a CD and say, "this is what you need to get onto the internet." The CD would have everything on it, including the browser, with no FTP required. We can also pile up CDs in Dixons, Currys and PC World; customers would pick them up as they walk around the stores. The other important component was the first page the customer sees when they get onto the internet. At the moment, other people are making money from our customers. I thought if our portal address burnt into the browser, our customers would see our website first, and we could control what's on our portal. Great idea, but what do I know about the technology required to power an ISP? The answer was nothing. I came up with a plan to outsource the technology and let them worry about the servers and modems. We also don't need any marketing because we have millions of people walking in our shops every week, simple, what a great idea. All my Life, I'd dreamt about becoming an entrepreneur. I read many books and magazines about how ordinary people had become successful because they dared to do something with their ideas. Maybe this was my moment. So, off I went to see the MD of PC World to tell him about my great idea. He listened and said, "No, let's focus on growing PC World and opening more shops." I was devastated that he didn't get my great idea. I almost gave up until I read an article in Vanity Fair about the Steve Jobs and Bill Gates of this world. One part talked about Ted Turner, the founder of CNN, the first 24 hour news channel. "Life's all about doing the obvious before it becomes obvious to everyone else because by the time it becomes obvious to everyone else, it's too late because people like Ted have done it, and the other guys haven't. So I mean, what possible reason did Ted have to start CNN, a 24 hours news channel? It blows your mind." When I read it, I thought, just because this guy didn't get it, it doesn't mean that my idea is bad. It's he can't see the obvious. Eventually, through our largest supplier, Packard Bell, I met our group CEO, John Clare, and told him about my idea. He listened and said, "I've got no idea if it will work, but Dixons have to be in the internet business." So, with a yes from the CEO, I started to work with the corporate development department to plan the launch of an ISP in Dixons, Currys and PC World. After getting the yes from Dixons, I started to work with Mark Danby from the Dixons Corporate Development Department on the business plan. We guessed all sorts of numbers, and once we finished it and everyone was happy, we put the business plan in the drawer and never touched it again. We chose a Leeds based company, Planet Online, to outsource our technology. It came about through a chance meeting at Leeds Utd. At the time, Packard Bell was the shirt sponsor of Leeds Utd, and the MD of Packard Bell got talking to the MD of Planet at a football match. He told him that we were looking for a technology partner, which led to meetings, and a deal was struck. The MD and Owner of Planet was Peter Wilkinson. He showed me around and introduced me to the key people. Philip Taysom's CTO would be the key man in this project since his team had to make everything work. David Watt was the project manager, and Rob Wilmot worked for Philip, building websites, and he would be building our website. So, off to work we went to build the technology and the portal. Philip was stressed trying to get enough bandwidth capacity, modems and the sign-up software ready for an ISP of this size. The name I came up with for our new ISP was Channel 6. I thought we would be the UK's sixth channel. We bought the domains and started doing content deals to fill the site. Everything was going well, and by April 1998, we were almost finished. The business model was like everyone else at the time, £10 a month, and we would have made a considerable margin on that. The only problem was that Dixons were dragging their feet, and we had no firm date to launch Channel 6. Then everything changed. In June 1998, BT announced a new ISP, 'BT Click', a local rate phone call plus a penny a minute. When I read the press release, I thought, who will pay a £10 month when you can 'pay as you go,' we're dead even before we've launched Channel 6. I went to see Peter to talk about BT Click, and we agreed we had to come up with something as good or better than BT Click. A week later, Peter called a meeting at the Planet London office. At the meeting were Peter, David Watt, John Pluthero (head of Dixons Corporate Development), Mark Danby and me. Peter announced that instead of charging £10 a month, we could go free and make money from the local rate phone call. When BT was privatised, the rule was that BT had to share that money when a call starts on one network and finishes on another. It's called an interconnect fee. Philip Taysom's network engineers Cliff Wood and John Murray figured with enough minutes, we could make more money from the interconnect fee than a fixed monthly subscription. That changed everything. It makes things even simpler, with no direct debits to set up, and everything else can stay the same. So, we decided to change the business model and make it a free ISP; things moved faster. Someone in Dixons suggested we change the name of the service to 'Freeserve,' similar to CompuServe. I wasn't happy with that because we might not be free in the future. This guy said to me, "Don't worry, the Carphone Warehouse doesn't sell car phones and is not a warehouse," and with that, we agreed to change the name from Channel 6 to Freeserve. We designed a new logo and took the Channel 6 logo off the website, and replaced it with the Freeserve logo; it took ten minutes. The only problem was that someone in Norway owned Freeserve.com. So we registered all the other domains and decided to launch as Freeserve.net. However, I thought we should own Freeserve.com, so we offered the guy in Norway who owned Freeserve.com £2,500 for his domain, and he accepted. He thought Ajaz Ahmed in Huddersfield was buying it; he didn't know that Dixons was behind it. We only managed to get it transferred to me the day before the Freeserve launch. I've always wondered what he must have thought when he saw the press the day after our launch. I've got to stress that we were not the first free ISP in the country. At least two others launched free ISPs before us, Connect Free and X-Stream, so we needed to be different. We decided to give free email and webspace even though few people knew what to do with webspace, but it allowed us to claim, "The UK's first fully-featured free ISP." Dixons called a press conference for 11am, 22nd September 1998, in the FT building in London to announce the launch of Freeserve. The response was great, but the journalist tried to find faults. Some focused on the £1 a minute support line. We priced it to stop people from calling support because Freeserve was simple; we thought users wouldn't need much help because the installation was so easy. I remember the BBC going to AOL to ask them what they thought of this new service, and they kept on talking about all sorts of things that AOL did better than Freeserve. They rejected our business model, "it's not what customers want," they said. The BBC had a news website at that time, and they used it to announce our new service, read the story on the old site, how different the site looks now. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/177467.stm The country went wild, and people were rushing into Dixons, Currys and PC World stores to pick up CD's. They loved it because there was no commitment. If you like it, carry on using it. If you don't like it, don't use it. Philip and his team were under even more pressure to keep the network running, with modems coming straight from the airport to plug into the servers just in time. Peter sold Planet to Energis (which was later bought by Cable & Wireless) around the time of our launch. It didn't make any difference to us since Peter or Planet didn't have a stake in Freeserve. The minutes continued going up, and the money from BT kept rolling in. The model worked beautifully. We had no marketing costs and what people didn't realise was, there were only two people on the payroll, me and Mark Danby. Mark worked from Dixons head office, and I borrowed a desk at Planet. Our costs were next to nothing. I bought a PO Box in Leeds from the Post Office and put that address on the website and CD's to re-direct the post in the future. We needed someone to answer the increasing number of customer emails. I asked a Dixons shop manager that I had known for many years if he wanted to work for us, he said yes, and Chris Fletcher became our first hire. We needed our own office and moved to 31 The Calls, in the trendy part of Leeds. I've always liked IKEA, so I went to IKEA Birstall and bought the office furniture, it looked great. When we moved, Rob decided that he wanted to work for us. He joined us at the end of November initially for three days a week, moving to five as we got busier. By December, we were already the largest ISP in the UK, employing just a hand full of people. Mark was the General Manager, Rob looked after the website, Chris answered all the email, and I looked after business development. A few weeks after the launch, we got a call from the Daily Mirror newspaper asking to see us. Mark and I went down to see them. After a cup of tea, the Operations Director said, "I'll get to the point, we like what you're doing, and we want to buy half the company." We both sat there looking at each other, and I said: "We don't want to sell Freeserve, we don't need any money or your distribution channels." He wasn't happy, and we left. I said to Mark outside his office, "I bet we could have got £20m," little did we know. At the beginning of 1999, the dot.com boom had started. All of a sudden, there was a lot more people on the internet. As a result, there was now a bigger market for start-ups to sell their products or services. Everyone had a business plan to make them a fortune which meant everyone wanted to talk to me, and everyone wanted to be on the Freeserve website. People figured that they could raise more money or float their business if they had an agreement with Freeserve. It got so bad that I had to take my mobile number off my business cards; the only way to contact was by email or the office number. I'd drawn up a list of channels for the website like news, sport, shopping, travel, money, etc. Many companies wanted to be on our site. We were in a good position.

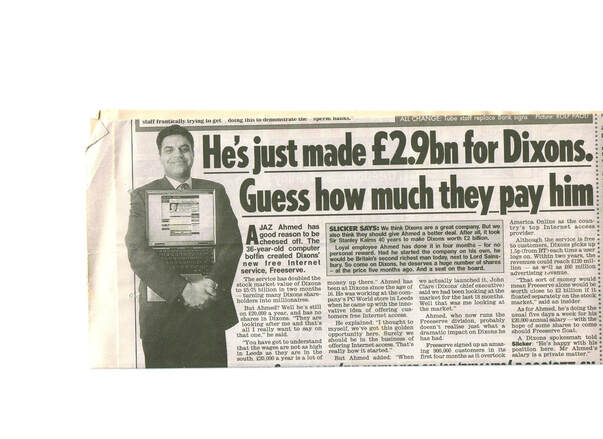

The business was booming. In early 1999, Dixons decided they wanted to separate Freeserve from the main group and float the company. John Pluthero, who was now the Head of Service and Distribution in the Dixons group, was brought in as the CEO to do the complicated and challenging job of getting Freeserve ready to float on the stock market. One problem was that we didn't employ many people. So we set about hiring more people, and if you look at the prospectus, it says 'average number of employees, 12.' It was also the right time to switch from Freeserve.net to Freeserve.com. We floated on the London stock exchange and the NASDAQ at the end of July 1999 with a market cap of £1.5bn, and we were only ten months old. The share price kept going up, and soon after, we overtook our parent company, Dixons, and even entered the FTSE 100. At our peak, we were worth an amazing £9bn. That's what you call a boom. The business kept on growing and getting more complicated. Rob had to stand to one side because he didn't have the experience. Stratis Scleparis, the CTO at AOL, joined us as our CTO. He later became the CTO at BT. Fake news about me in The Daily Mirror.

Internet Age magazine gave me an award, and at the end of the lengthy interview, the journalist asked me, "How much do you get paid?" I said, "It's not something I want to talk about", and then for some stupid reason, I said, "You've got to remember £20,000 goes a long way in Leeds." The Daily Mirror saw this and wrote this article, "He's just £2.9bn for Dixons. Guess how much they pay him. He's still on £20,000 a year" Dixons quickly arranged for Hugh Pym from the BBC news to give me some media training. For months people I knew stopped me on the street to ask if that's what I really got paid. I was paid a lot more as a manager. The Mirror printed an apology the day after, but no one read that. Like all good things, the boom was followed by a crash, and our share price started to go down. Dixons decided that it would be an excellent time to sell the business. A deal for £6bn fell through. In the end, Freeserve was sold to France Telecom in April 2001 for £1.65bn. Not bad for a three-year-old company. A couple of months after the sale, I sold my shares and left Freeserve to start a new chapter of my Life. How old was I when all this happened? I was just 35 when Freeserve launched and 38 when Freeserve was sold, and when I sold my shares and left. Where is Freeserve now? France Telecom made a big mistake, they changed the name from Freeserve to Wanadoo, which is their ISP in France, and when that didn't work, it became Orange Broadband. I've never written about the Freeserve story before because some people remember it differently, and certain people wildly exaggerate the role they played. From many comments on LinkedIn where this story first appeared, the people who were there at the beginning, people who helped me make Freeserve a reality and kick start the dot.com boom in this country. People who can confirm how it all started. How do you make lots of money by giving it away? You don't pay anything for most of the things you do on the internet. The key is to get lots of people to use your service, and suddenly, you are worth lots of money. We made lots of money because the first thing customers saw when they opened their browser was our website. We made £2.5m a year just from the search engine and many more millions from our other channels because we had lots of traffic. We got a fraction of a penny from each minute, but when you have more than a billion minutes a month, that's a lot of fractions. Our business model was to 'collect small amounts of money from many people.' Apple have the same model, you hear a nice tune, and 99p later is yours. The biggest thing people underestimate in business is how difficult it is to acquire a customer. "If you build it, they will come," no, they won't. It might cost you more money to acquire the customer than you'll make from them. We were not the first free ISP, and the reason we were more successful than the others was because it cost us nothing to acquire the customer. Our route to market is what made us different, millions of people were walking around our shops picking up CDs, we didn't have to buy expensive adverts. I recently met the Founder of PlusNet, who sold it to BT. He was amazed that we did the direct opposite of what they did. They built their network, wrote their code, employed lot's more people and spent a fortune acquiring customers. Our model was much better. Freeserve has been a fantastic journey. I've met everyone from the Queen to the President of the United States and many famous personalities. Freeserve has touched many people's lives; for many people, Freeserve was the first time they experienced the internet. People made money from buying and selling shares at the right time. I sat next to a manager at a Dixons sales conference, and she told me she'd bought a house because the Dixons share price in her share-save scheme had gone up so much. I met a Dixons manager in Leeds who told me he had bought a Rolls Royce when I asked him "why?" After many years he wanted to start his own business, chauffeur-driven wedding cars. He said that he left Dixons, "well done, John," I said. I've received a 'British Empire Medal' from the Queen, not for Freeserve but for helping young people in schools and colleges. I've met some fantastic people that have helped me on my journey. Some of those people have gone on to become good friends. All this happened because no one in PC World Leeds could tell me how to get onto the internet, and I did something about it so people could get onto the internet. Thank you for reading the Freeserve story. This article is not the book. It's a shortened version of the story. So many other things happened, like Packard Bell planned to be a partner, but they dropped out before Freeserve launched. I opened a successful Indian takeaway before Freeserve started, but that story is for another day. It may sound obvious, but, if you want to be successful, make something or provide a service that people want, it's that simple.

|